By Louise Delmotte

For the first time in more than 50 years, the upcoming Oscars ceremony will not be aired in Hong Kong. TVB’s decision not to pursue the broadcasting rights might have been triggered by the nomination of the documentary Do Not Split, which looks back on the 2019 pro-democracy protests.

“How Beijing is dealing with our documentary is just the continuation of what we saw during the protests in Hong Kong. The room for democracy is shrinking a lot,” said the film director Anders Hammer on the day the decision was announced. “Obviously, it’s easy for a foreign filmmaker like me to stand against Beijing. If I had been a Hong Kong person living in Hong Kong, that would have been more difficult.”

Undaunted by the latest developments, a group of friends who refused to be identified organised a secret screening of Inside the Red Brick Wall.

A small cafe whose owner is seen as pro-democracy was converted into a cinema for a night screening for dozens of people, with windows covered with thick dark plastic bags. “Some were weeping among the crowd – myself included,” said one attendee. “But we all tried to keep our emotions at bay. Some of my close friends were involved in the Poly U incident. They had no choice but to leave Hong Kong for good. And they still miss Hong Kong every day.”

The organisers of the event used to regularly attend community screenings during the 2019 protests. For them, film is a matter of remembrance and provides time to process memories. “What happened is indelible and the memories associated with the movement can’t be erased,” said the attendee. “The authorities don’t want us to remember but it’s our responsibility to do so.”

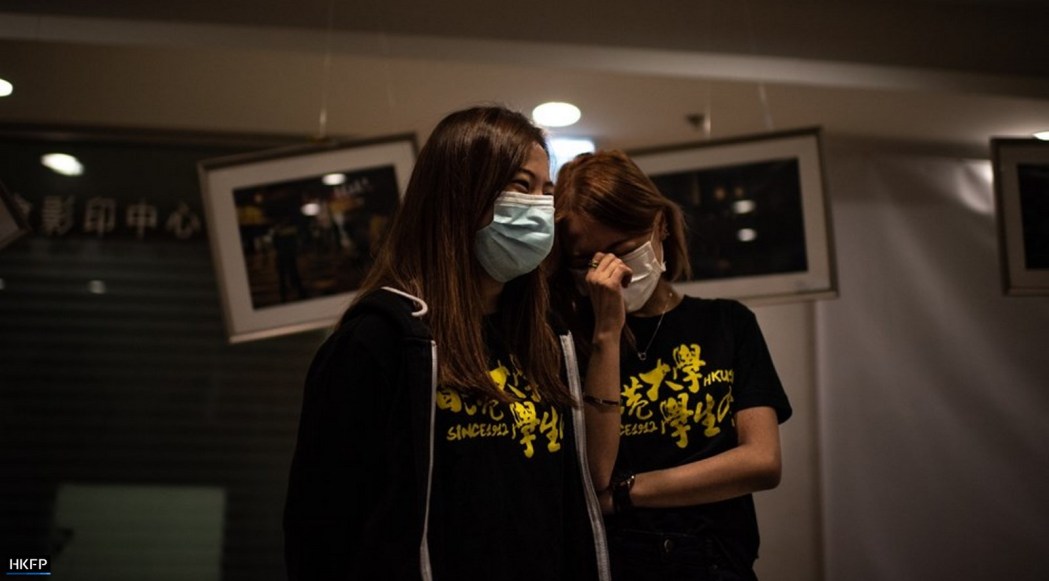

Back in February, the management of Hong Kong University urged the student union to cancel a screening of the documentary Lost in the Fumes, warning that they could face legal issues under the national security law. Yet the students pressed on.

The documentary explores the life of the pro-independence activist and HKU alumni Edward Leung. The student union organised a screening on the fifth anniversary of the 2016 Mong Kok unrest, for which Leung was jailed for six years. “This is a war between forgetting and remembering,” said the union vice president Tracy Cheng. “To remember and understand what happened is very important for the future of Hong Kong.”

The national security law broadly defines what it criminalises, making it difficult to ascertain if one is breaching the law. As of now, the students have not faced any repercussions.

As public screenings of any politically related movies now seem unlikely, some are seeking alternative means of access. After Golden Scene announced that it would not screen Inside the Red Brick Wall, requests for Netflix to make available the so-called sensitive films on its platform flooded social media.

Subscribe to HKFP's twice-weekly newsletter for a concise round-up of local news and our best coverage. Unsubscribe at any time - we will not pass on your data to third parties.

Processing… Success! You're on the list. Whoops! There was an error and we couldn't process your subscription. Please reload the page and try again.Nora Lam’s Lost In The Fumescan be watched on iTunes and Google Play, but the director fears that China’s increasing economic influence may hold streaming platforms back. Meanwhile, some filmmakers choose to broadcast their films for free online. One example is Do Not Split. “We will continue giving people the opportunity to watch it,” said Hammer.

Yet revenues generated by streaming platforms are not enough to sustain Hong Kong’s independent film industry. Filmmakers who create political documentaries also find themselves grappling with “blacklisting” issues.

“I just wanted to tell a story. I didn’t know it would become illegal. I don’t think it should be illegal. But that kind of thing stays on your profile. Personally, I think it’s hard for me to move beyond Lost in the Fumesbecause people are just very hesitant about working with me”, said Lam.

Local filmmaking is now a labour of love,said Dr Aaron Han Joon Magnan-Park, Assistant Professor in the Department of Comparative Literature at the University of Hong Kong, and there will be no financial rewards. “It’s hard because you’re taking a political stance and a political risk by making a Hong Kong-specific film. You basically say I’m not going to play by CEPA’s rules, at which point you limit what you can or cannot do in the future and sacrifice your career.”

CEPA is the abbreviation for the Hong Kong Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement concluded in 2003, the year when Hong Kong cinema had to financially connect with the mainland market. In a bid to boost co-productions, it has dramatically changed Hong Kong’s cinema outlook.

Since then, said Magnan-Park, “if you want to make money in Hong Kong, you have to make a film that makes China look good on the international stage and can pass government censorship.”

As China overtook the US to become the world’s largest movie market last year, the impact of its government’s censorship on films has reached far beyond its borders: “You cannot make the Chinese people or the CCP look bad,” said Magnan-Park. “If you’re a Hollywood filmmaker and you want to make money, you have to make a film that can be released in China. Otherwise half of your global profit is gone. It’s not only Hong Kong, it’s everyone.”

In Hong Kong, the national security law has only added to this economic pressure. The pro-Beijing paper Ta Kung Paorecently slammed the Hong Kong Arts Development Council for distributing funding to organisations that allegedly violate the new law. It listed the distributor of Lost in The Fumes, Ying E Chi, as one of those organisations. “Things are going to change for the worse very soon.” said Nora Lam, since her distributor may not get subsidies anymore.

Hong Kong cinema, she said, might lean towards a more “global filmmaking” trend in the future. Recently, she has been exploring the possibilities of finding funding outside of the city.

This is the direction that Blue Islandchose to take. To be released this June, the documentary about the Hong Kong protests has secured Uzumasa, Inc. in Japan as a production partner, alongside others in Europe and Asia. “I think there is support all around the world now. Producers overseas do care about Hong Kong, about what is happening. They want the Hong Kong story to be told by Hong Kong cinema and they expect something from us.” explained its director, Chan Tze Woon.

The team also launched a crowdfunding project last year to raise the remaining sum needed for production, which easily reached its target. “It’s very new to us. We didn’t expect it to be such a success. I think it’s because of what happened in Hong Kong, people just want to support films that tell their stories,” said Chan.

Under such impetus, a film’s success could be due to the support from the local community, which bolsters ties between filmmakers and their audience. “There was this volunteer we met after a screening; I think she distributed posters to more than a hundred shops. She is just an audience member!” said Leung Ming-kai and Kate Reilly, directors of Memories to Choke on, Drinks to Wash Them Down – an anthology film that explores everyday life in Hong Kong.

After every screening, they greet and thank their audience in person. “A lot of people start crying. They say that this film documents things they expect to be lost, and that they are grateful that this will serve as a record of small aspects of Hong Kong society that might disappear. That’s very common.”

Meanwhile, there has been a lukewarm response to mainland-made films in the city. Golden Scene started to distribute more local films in 2012 because of a greater appetite for them, said Felix Tsang. “The co-productions and the mainland films have different sensibilities. We don’t even speak the same language. It’s just facts: Chinese made films don’t do well in Hong Kong. And you can’t force people to like stuff that they don’t want to watch.”

Hong Kong’s political crises, including the protests, could account for audiences’ change in taste. More than two million adults have shown symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder following the 2019 civil unrest, a study published by HKU academics revealed last year. “Would they still be interested in a simple romance or a gangster movie after reading all the news in Hong Kong?” asked Nora Lam. “We have to relate to the time we are living in.”

Lam has often considered shifting her focus overseas, since she won’t experience any commercial success in Hong Kong. “But it’s very hard because what I create is influenced by where I live. Because if you are connected to this place, you care about this place enough to tell a story.”

For some independent filmmakers, the shrinking freedom of creative expression has fostered a new sense of duty. Chan Tze Woon, who grew up in Hong Kong, has witnessed the city changing since he started making documentaries during the Umbrella Movement in 2014. Filmmaking could be one of the handful of mediums to organise seemingly fractured historical events into a coherent narrative.

Tze Woon finds inspiration from the Iranian film industry, which has been thriving despite heavy censorship that dates back to the 1979 Islamic Revolution. “I’ve never felt more direct censorship than now, but it is the moment when a new generation of filmmakers have to ask themselves: how to tell a story under limitations? Sometimes, you can create a movie that is much better than if there was no censorship.”

Hong Kong cinema has always been in crisis, said Dr Fiona Law Assistant Professor in the Department of Comparative Literature at HKU.“But In Cantonese, the word for crisis is the combination of risk and opportunity, meaning that it’s also about how people handle the risk and seize consequential opportunities. Hong Kong cinema has always had a very strong will to survive – facing death is not an issue at all.”

As long as the local culture resonates with audiences, Hong Kong films may still find a market. “Generations later will still be speaking Cantonese, and I hope that the Hong Kong culture can just keep going,”said Felix Tsang. “But I guess this is starting to change as well.”

To re-cultivate patriotism, the government has introduced a new national education curriculum. Recently, the Education Bureau announced that it will distribute a series of books named My Home is Chinato all primary and secondary schools as supplementary teaching material. “Getting bored of Hollywood and Disney movies or animations? Wonderful movies from the Belt and Road are available,” one of the books reads.

Despite the uncertainties, Nora Lam said the worst times often trigger the best stories. “I don’t care about knowing whether Hong Kong cinema is dead, I do care about whether I’m dead or not… if I’m not dead, then there’ll still be Hong Kong films because I’ll keep doing it.”

Louise Delmotte is a final year undergraduate at the University of Hong Kong studying politics and business. Originally from France, she has been living in and covering Hong Kong since summer 2019.